Essay

The Isles of the Immortals on a Spring Morning in the collection of the Seattle Art Museum, a landscape in the blue-and-green style which reveals major characteristics of a Taoist paradise, has rightly fascinated its viewers for centuries.

As the handscroll is unrolled from right to left, a panoramic view of an otherworldly realm unfolds. Measuring 7 11/16 x 38 1/4 in. (19.5 x 97.2 cm), the composition of the painting is rather unconventional. When the scroll opens, instead of open space, the first section features mountains, trees, open pavilions, and travelers. Such a dense composition can be compared to an even earlier Taoist landscape, titled Mountains of the Immortals by Chen Ruyan陳汝言 (ca. 1331–1371), now in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art.See Wai-kam Ho; William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts.; Cleveland Museum of Art.; et al, Eight dynasties of Chinese painting: the collections of the Nelson Gallery-Atkins Museum, Kansas City, and the Cleveland Museum of Art (Cleveland, Ohio: Cleveland Museum of Art in cooperation with Indiana University Press; Bloomington, Ind.: Distributed by Indiana University Press, 1980): 139-40. Chen depicts a community of Taoist practitioners, whereas The Isles of the Immortals on a Spring Morning, in contrast, emphasizes natural scenery rather than human activity. In the Seattle scroll, only two travelers are present, conversing on a bridge between an open pavilion and their dwelling. Their journey is symbolic, traveling across myriad mountains to the Isles of the Immortals.

In the second half of the scroll, space dramatically opens up. Sheer peaks and light swirling mist guide the view leftward, where just the roofs of palace buildings are barely visible, the Isles being shrouded in the heavy morning mist of China’s East Sea. The striking contrast between the two sections creates a dynamic composition of an appealing spiritual realm.

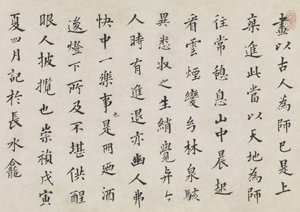

In the upper left corner, at the end of the painting, is an inscription: “Spring Dawns on Peng[lai]-Ying[zhou], painted by Wang Jianzhang, a layperson who makes a living in fields of ink, in the third month of the wuyin year (1638) of the Chongzheng era (1627–1644).”

The Isles of Penglai and Yingzhou were the places where the First Emperor Qin Shi Huangdi (259 b.c.–210 b.c.) sent his envoys to seek the elixir of immortality. For the owner of this scroll, both conceptual and visual visits to such spirit isles must have been most delightful, as they continued to be for subsequent collectors. One of the seals engraved by Tetsujō Kuwana桑名鐵城 (1864–1938), the last private owner of the scroll, states “Penglai is my home.”See Kuwana’s seal in www.sealbank.net, accessed 06/27/2011.

During the time when landscape was becoming an increasingly important component of Chinese art, Xie He, a fifth-century C.E. painter, proclaimed a lofty goal for the art of painting:

“Now…of all who draw pictures there is not one but may illustrate some exhortation or warning, or show [the causes for] the rise or fall [of some dynasty], and the solitudes and silences of a thousand years may be seen as in a mirror by merely opening a scroll.” William Reynolds Beal Acker, Some Tang and Pre-Tang Texts on Chinese Painting (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1954-74): 3.

圖繪者,莫不明勸戒、著升沉,千載寂寥,披圖可鑒。

Though not a landscape painter himself, Xie underscored the great pleasure that the transcendental creative process and appreciation of art brought forth.

From the tenth century onwards, spiritual connotations faded as landscape entered the mainstream of Chinese painting. A harmonious relationship between man and nature was embodied in specific types or genres of landscape painting, such as landscape featuring a scholar’s studio, family estates, travelers, or spiritual worlds. It is in this light that The Isles of the Immortals on a Spring Morning offered a transportable scene to evoke the visual journey to the realm of the immortals.

To enhance the handscroll’s spiritual dimension, Wang Jianzhang made use of the blue-and-green style in his depiction of a Taoist paradise, in contrast to the contemporary monochromatic style seen in his other extant works of art. In addition, he used gold-flecked paper, a distinctively archaic feature, the shining elements appropriate to and signifying the divine character of a religious theme. Moreover, his brushwork, which swiftly defines contours of trees, rocks, and clouds, has a most evocative effect on the imagination.

A professional artist from Quanzhou, Fujian Province, Wang Jianzhang was little known in pre-twentieth century Chinese literature on painting. However, Wang was favored by Japanese collectors since the nineteenth century, partly due to his alleged visit to Japan and partly due to his connection to another Fujian artist, Zhang Ruitu (1570–1644), who was appreciated for his literati style. In the early twentieth century several Chinese collectors brought Wang’s paintings to Japan to cater to the demands of its art market.For Wang Jianzhang’s popularity in modern Japanese collectors’ circles, see Itakura Masaaki, “Jinshi, jindai Riben de Zhongguo hua jianshang yu huajia xingxiang de bianrong, yi Mingmo Qingchu huajia Wang Jianzhang wei li” (Japanese connoisseurship of Chinese painting and the changing images of painters: The case of the late Ming-early Qing painter Wang Jianzhang), in Gaoxiong shili meishuguan, Shibian xingxiang liufen: Zhongguo jindai huihua 1796-1949 (Turmoil, Representation and Trends: Modern Chinese Painting, 1796-1949), (Gaoxiong: Gaoxiong shili meishuguan, 2007): 137-52. It is uncertain where Mr. Kuwana acquired this scroll,Kuwana Tetsujō first published the scroll in Kyūka Inshitsu kanzō garoku (Kyōto: Kuwana Tetsujō, 1920) v. 1; :32. but the scroll has a label inscribed by Deng Shi 鄧實 (1877–1951), a Cantonese scholar-entrepreneur who resided in Shanghai. And the inscriptions by Kichidō Utsumi内海吉堂(1852–1925) and Shiichi Tajima田島志一 (1869-?) on the scroll indicate that it had entered Mr. Kuwana’s collection no later than 1912.

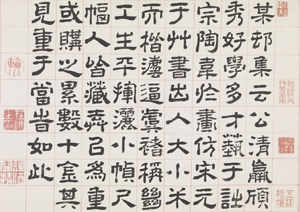

Considering the stylistic difference of the Seattle scroll and other works such as Searching for a Poem in the Mountain Shake by Wang Jianzhang in the Ching Yüan Chai Collection,See James Cahill; University of California, Berkeley. University Art Museum.; Fogg Art Museum.; California. University. Dept. of Art and History of Art. The Restless landscape: Chinese painting of the Late Ming period, (Berkeley, University Art Museum, 1971): 112, pl. 47, and its note on: 166. the handscroll’s attribution remains open to question. Except for the inscription and three seals by Wang, only one unidentified seal and one seal of Fan Shunan范澍楠 (zi Chunfang春舫), a mid-nineteenth-century scholar, are found on the painting itself. An extension of mounting at the beginning of the scroll has fifteen seals of eminent Chinese collectors and court painters from the seventeenth to the early eighteenth century. These are at odds with the obscurity of Wang Jianzhang. Most likely, this piece of silk with seals was taken from a different painting or calligraphy and attached to the Seattle scroll by an unidentified art dealer. Whether or not it is truly by Wang Jianzhang, The Isles of the Immortals on a Spring Morning became known when it was published in Mr.Kuwana’s 1920 catalogue. Since its acquisition by the Seattle Art Museum in 1951, the scroll has attracted increasing attention from viewers all over the world as a fine example of the realm of the immortals in Chinese landscape painting.The record of its publication after 1920 is as follows: Osvald Sirén, A history of later Chinese painting, (London: The Medici Society, 1938), v.I, :237; Detroit Institute of Arts catalogue, Arts of the Ming Dynasty, (Detroit, 1952), no. 61; Sherman E. Lee, Chinese Landscape Painting, (Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art, 1954), no. 78; Sherman E. Lee, “Ming and Ch’ing Landscape Painting,” in Ars Orientalis, II, 1957, : 478-9, Pl. 9; James Cahill ed., Relentless Landscape: Chinese Landscape Painting of the Late Ming Period, (Berkeley: University Art Museum, Berkeley, 1971): 166, pl. 49; Kiyohiko Munakata, Sacred Mountains in Chinese Art (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1991): 136; and Teisuke Toda, Hiromitsu Ogawa, Chūgoku kaiga sōgō zuroku. Zokuhen (Comprehensive Illustrated Catalogue of Chinese Paintings, second series), (Tōkyō: Tōkyō Daigaku Tōyō Bunka Kenkyūjo, 1998), v. 1, A55-039.

© 2013 by the Seattle Art Museum

Questions for thought

Answers

| Add an answerAdd Answer:

overview

Wang Jianzhang王建章

Quick Facts about the Artist

inscriptions and seals

essay

The Isles of the Immortals on a Spring Morning in the collection of the Seattle Art Museum, a landscape in the blue-and-green style which reveals major characteristics of a Taoist paradise, has rightly fascinated its viewers for centuries. As the handscroll is unrolled from right to left, a panoramic view of an otherworldly realm unfolds.