Essay

Being at that stage in my life when nearly any name, any familiar work of art, calls up a cluster of distant memories, I begin this essay with those attached to Shao Mi’s邵彌 (ca. 1594–1642) Landscape of Dreams album of 1638. It was owned in the 1960s by the French scholar-dealer Jean-Pierre Dubosc, and I may have seen it already when I spent time with him while traveling in Europe in early 1956. In any case, it was one of the late Ming paintings that I recommended highly to the 1970 graduate seminar at U.C. Berkeley that produced the exhibition and catalogue titled The Restless Landscape: Chinese Painting of the Late Ming Period (Berkeley, University Art Museum, 1971), in which five leaves from the album were shown (cat. No. 19), and the great first leaf reproduced in color (p. 72).

By then it was in the collection of the Seattle Art Museum; but it had been acquired by them only after I had worked unsuccessfully to have it bought by the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco. Some funds remained after the big international symposium held in the late 1960s celebrating the opening of the Brundage Collection, and it was decided that they would be used for the purchase of a work of art. The committee charged with choosing that work included, unfortunately, both myself and Yvon d’Argencé, Director of the Asian Art Museum and Brundage’s protégé whom Brundage described as “the son I never had,” (setting him above the two illegitimate and unacknowledged sons he did have). And Yvon, regarding me as a potential threat to his dominance within the museum, chose to oppose whatever I proposed. The loss to San Francisco of the entire Contag Collection of Chinese paintings was the worst outcome of that attitude, but it found quite a few other channels of expression. When I proposed the purchase of the Shao Mi album to the post-symposium committee, Yvon flatly turned it down as not worth acquiring, using his familiar argument about “bad condition”—extensive repair and repainting that only he could see, and that in fact was not there. The album was lost to San Francisco and gained by Seattle.

My engagement with the album continued, however, with the section on it in the Restless Landscape catalogue. Although the entry is credited to then-student Lucy Lo-hwa Yang, it nonetheless bears the marks of my coaching as I have long been interested in researching the work. I wrote about it again in my book The Distant Mountains: Chinese Painting of the Late Ming Dynasty.Cahill, James, The Distant Mountains: Chinese Painting of the Late Ming Dynasty (New York and Tokyo, Weatherhill, 1982, pp. 61-2, Colorplate 5 and Fig. 18.) It is a pleasure, then, to return to looking seriously once more at these familiar but still mysterious leaves.

The Painting Album in China

The form this work takes, the album of paintings, has itself been a special concern of mine throughout my career. My first public lecture, given at the Freer Gallery of Art in 1957 after my return from a period in Japan and Europe, was titled “Painting Albums in China and Japan” and was built mainly around five albums: two recent acquisitions by the Freer, albums by Bada Shanren 八大山人 (1626–1705) and Hua Yan華嵒 (1682–1756), and three that I had photographed in the collection of the great novelist Kawabata Yasunari, during a memorable overnight stay at his house in Kamakura.The lecture given at the Freer is CLP 127 in the “Cahill Lectures and Papers” series on my website, jamescahill.info; the overnight stay at Kawabata’s house is recounted in the “Responses and Reminiscences” series, no. 44, “Kawabata Yasunari.” The Luo Ping album is discussed briefly, with one leaf reproduced, in my book The Lyric Journey: Poetic Painting in China and Japan (Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1996), p. 142-3 and Fig. 2-42. The Kawabata albums included the great pair by Ikeno Taiga池大雅(1723–1776) and Yosa Buson与謝 蕪村(1716–1783) titled Jûben Jûgi (Ten Conveniences, Ten Pleasures), painted in 1771, and an album of pictures after Song-period poems by Luo Ping 羅聘 (1733-99 ), an album that would later be acquired by the Freer, when Kawabata—selling it through the dealer Mayuyama Ryûsendô—directed him to offer it first to the Freer because of my special fondness for it. It was the excitement I felt upon leafing through another great Japanese work in album form, Uragami Gyokudô’s浦上玉堂(1745–1820) Album of Mists and Clouds painted in 1811, before it was shown on exhibition in New York, that first excited my enthusiasm for Nanga-school painting; the album would later be included in the first exhibition of that school outside Japan, my Scholar Painters of Japan: the Nanga School Cahill, James. Scholar Painters of Japan: the Nanga School (New York, Asia House Gallery, 1972).(New York, Asia House Gallery, 1972), in which the album was included (no. 35).

The special attraction of painting albums for me as works to lecture and write about arose in some part, I think, from the special problems they presented to the writer or lecturer. The ideal way of viewing them was to sit at a table with a fine painting album before you, turning the leaves at leisure; but that experience obviously could not be offered to one’s listeners and readers (the album could not be subjected to that much wear-and-tear). This meant that one had to convey the pleasures it offered in some other way: through showing and talking about a series of slides in a lecture, or reproducing and writing about all the leaves in an article or book. The latter option is not ordinarily open: few publishers permit that many reproductions from a single work, when one is writing about an artist or a school or a subject involving many works. I developed, and taught my students to use, what I took to be effective ways of getting around this problem. Similarly, the experience of viewing a hanging scroll, first from a distance and then part by part as one moved in closer, could be approximated with the showing of slides of the whole and details; that of rolling a handscroll and viewing successive sections was easily turned into a succession of slides or reproductions. Teachers cannot experience works of art without considering, at least on some level, how they will teach them.

About Shao Mi

The fullest and best biographical account of Shao Mi in English is that of Ellen Laing, written for the Dictionary of Ming Biography.Ellen Laing, in L. Carrington Goodrich, ed., Dictionary of Ming Biography, 1368-1644, New York, Columbia U. Press, 1976, pp. 1166-68. It can be summarized briefly here. His period of activity, from extant dated works, is from the 1620s to the early 1640s. Born in Suzhou into gentility—his father was a physician—Shao Mi was a learned and cultivated man, but ill health from childhood precluded any attempt at an official career. He must have had a source of steady income, perhaps from inherited property, and appears to have lived comfortably enough, collecting paintings and antiquities. A colleague describes him as being “as thin as a yellow crane and as free as a seagull.” He was seriously afflicted from middle age with a lung disease and read widely in medical books in search of a cure, but without success.

His situation in late Ming painting history was ambivalent: on one hand, a native of Suzhou and heir to its great tradition of painting who admired and imitated Tang Yin 唐寅 (1470–1523) and Wen Zhengming文徵明 (1470–1559); on the other, a literatus with close ties to the rival movement in Songjiang led by Dong Qichang董其昌 (1555–1636) and his followers. A selection of Shao Mi’s works could be made to illustrate either tendency: an undated but presumably early album in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, includes leaves in the manners of his Suzhou forebears (fig. 1);See my The Distant Mountains, figs. 16 and 17. an album of landscapes he painted in 1634 contains an admiring colophon by Dong Qichang, and a handscroll from 1640 imitates Dong and other Songjiang artists so closely that it might be taken for a work by one of that group (fig. 2).

The Seattle album, painted in 1638, is closer in style to works of his earlier period, and is happily free of any signs of his adherence to the new orthodoxy developing in Songjiang. At least one leaf, the second, shows visible affinities with the Wen Zhengming tradition in its theme (friend arriving to visit retired scholar) and its materials, although these materials are radically rearranged into an unsettling composition that is very unlike any of Wen’s. The album reveals Shao Mi altogether poised as an independent, able to invent and imagine freely.

Innovations in Late Ming Landscape Albums

A quick look over the uses of the painting album up to Shao Mi’s time will help in defining his achievement. It had begun as a kind of illustrated teaching manual, or collection of pictures of some subject for imitation by students; a book of blossoming plum pictures was composed and published already in the late Song, the Meihua xishen pu 梅花喜神谱; examples from the Yuan include well-known manuals of ink-bamboo by Li Kan李衎 (1245–1320) in the early Yuan and Wu Zhen吳鎮 (1280–1354) in late Yuan.Since information on these can easily be found, I am not giving detailed references. By the time of Shen Zhou沈周 (1427–1509) in the fifteenth century, albums made up of scenes from some garden or special locale were common; Shen’s Twelve Views of the Tiger Hill album in the Cleveland Museum of Art is a good example. By late Ming, artists in Songjiang such as Dong Qichang and Shen Shichong沈士充 (active ca. 1605–1640) were painting large numbers of albums made up of landscapes “in the styles of” a series of canonical old masters, and this type was produced endlessly from then on by artists of the Orthodox school. For at least one viewer of hundreds of these later examples, the present writer, theFor references to these and other works by Shao Mi, see my discussion of his stylistic development in Distant Mountains, pp. 60-61. The 1634 album was published as Shao Sengmi shanshui ce邵僧彌山水冊, by Shanghai Commercial Press in 1939, and later by Taiwan Commercial Press in 1976.y are mostly repetitive and boring.For a counter-argument to the idea that more difficult kinds of connoisseurship represent a higher taste, using just this kind of album as example, see my book The Lyric Journey, pp. 78-80. My chapter on Dong Qichang in The Distant Mountains, on the other hand, discusses the new practice of fang or creative imitation, with examples, as an aesthetically stimulating practice.

For the best artists, however, from Shen Zhou’s time on, the album of landscapes permitted a greater freedom of compositional construction, since any single leaf within a succession of leaves need not exhibit the self-sufficiency and stability normally required of a hanging scroll. Late Ming artists such as Dong Qichang, Zhao Zuo趙左 (active ca. 1610-30), and Shen Shichong were exploiting this openness in brilliantly inventive leaves that sometimes distorted space, pushing the materials of the painting into one corner or stringing them diagonally across the picture area; Shen Shichong’s Twelve Scenes from a Country Garden album of 1625 is a good example (fig. 3).See my Distant Mountains fig. 32 for a leaf from this album. Shao Mi must have been familiar with these developments, and in his 1638 album exploited the new compositional freedom they offered.

But, whatever his dependence on precedents may have been in his compositions, Shao Mi chose to characterize his pictures in what was, I believe, a new way: as the landscapes of dreams. He writes this couplet on the tenth and last leaf:

Divine realms where immortals are concealed,

Once came in a dream upon these shores.A more literal translation is provided in the ‘Inscriptions’ section.

This is followed by the artist’s signature and a date corresponding to the fourth month of 1638. The question of how far the claim of “dream realms” was an artist’s stratagem, and how far a real explanation of how Shao Mi conceived these images, is probably beyond exploration, but we can keep it in mind as we look at the ten leaves, one by one.

Further Documentation

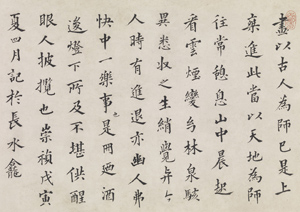

A longer inscription by the artist is on an additional leaf. It reads:

“In painting, it is already the superior way to take the ancients to be one's teachers. Even better is to take nature as one's teacher. When I resided in the mountains, at dawn I would watch the ever-changing movements of mist and clouds. And I was also awed by the differing [appearances of] forests and springs. All these, I gathered [in my paintings] on raw silk. I feel, if I compare [my works] with those of my contemporaries, some are a step forward, others a step backward. As a hermit, I find this [painting] a joyous aspect of an otherwise unhappy existence. This album, having been done after drinking and by lamplight, is not worthy of being seen by a sober man.”

In summer, the fourth month of the wuyin year (1638) at [studio] Changshuikan.

—Guachou Shao Mi.

A colophon by an unidentified writer on another leaf copies a passage concerning Shao Mi from Meicun ji, the literary works of Wu Weiye吳偉業 (1609–1671). It speaks of Shao’s refinement of character, his learning and talent in the arts, his imitation of Song and Yuan masters in painting, his achievements in calligraphy—these are attributes that linked Shao Mi to the ideal artist of the Orthodox school, to which Wu Weiye was an adherent. It ends with the statement that people who owned even small paintings by Shao Mi during his lifetime treasured them, and sold them for high prices if at all: this, Wu concludes, indicates how highly he was valued in his time.

Together, these colophons serve to place Shao Mi in the ambiguous position he occupied in late Ming painting, as described above: a native of Suzhou with strong ties to its painting tradition and who was nonetheless drawn to the new, more rigorous mode of landscape that would develop into the Orthodox school manner. His opening statement about taking the old masters as one’s teachers is a nod to that orthodoxy; but then, to characterize his album as "not worthy of being seen by a sober man" may be taken as an acknowledgement of its non-adherence—for which we can be thankful—to that new mode. In fact, it draws freely on both the Suzhou and Songjiang traditions without being subservient to either of them.

Shao Mi’s Album: the Ten Leaves

The order of the leaves followed here is that presently assigned them by the Seattle Art Museum; it does not correspond to the numberings in the previous publications—the leaves are in fact unnumbered, and can be arranged in any order, provided only that the inscribed leaf is last. How the relationship among the individual leaves was originally conceived is not clear, and wasn’t meant to be—the artist was not that consistent.

Treatments of these leaves, including those by myself and my students, have offered compositional analyses that try to account for the unsettling effects they have on viewers. Instead of doing that again—seriously interested readers can find those earlier accounts in books—I want to try another approach, one suggested by the couplet that Shao Mi inscribed on the last leaf. If these are dreamlike “realms” where “immortals are concealed” or dwelling, then are we to imagine visiting them, following pictorial clues that the artist has provided? Does the album offer escape from the mundane world just as Shao Mi must have longed to escape his real, troubled existence? All the leaves contain some indicators of human habitation, or human passage: cliff-side paths with railings, steep ascents with stairs, buildings that are (at least to this viewer) often of an ambiguous character: houses, shrines, temples? And always the viewer is confronted and confounded with patterns that disrupt the simple reading, evoking “dreamlike” effects, removing us from the firmly traversable and easily intelligible world.

An important component in the construction of traditional landscape paintings in China—and one that guided the viewer’s visual readings of them—was the inclusion in the picture of indications of human passage: paths with steps and railings, viewing pavilions where one was to imagine stopping to rest, buildings that could be read as starting-points or destinations. Early landscapists took care to lay these out clearly, thus controlling to some degree the way their viewers read the pictures. In early monumental landscapes, for instance, secular dwellings or villages at the bottom were connected by a path to a temple seen above, setting a theme of spiritual ascent, with the inaccessible peak still further up. Later artists varied or altered this plan in too many ways to even summarize here.

By the late Ming, the most interesting landscapists were manipulating the old formulae in a diversity of ways. Wu Bin played on the monumental landscape convention with strangely distorted forms that encouraged old-style readings in their academically detailed rendering but frustrated any imagined passage between them. Dong Qichang scattered the conventional indicators of human movement and habitation sparsely around his landscapes without connecting them in any coherent way. Zhang Hong offered landscapes that reproduced, with unsettling visual truthfulness, what one might see at the place, but without mapping out how one might imagine entering the scene and moving around in it. How did Shao Mi play upon these long-established expectations of viewers of landscape imagery for his new, private purposes? A consideration of this aspect of each of the ten leaves will go far to answer that question, and will reveal details in them that usually escape notice.

The First Leaf—supposing that the present sequence is the original one, which is far from certain—already warns the viewer that these are not going to be comfortably traversable landscapes. At first glance, it appears to present a visionary image of a double peak rising above clouds, with no sign of human passage or habitation. In fact, it is only on close examination that one finds such indicators—and they are so slight, so ambiguous, that Shao Mi’s intent still remains unclear. Ascending the right edge of the smaller peak at left is a streak of unpainted paper, more or less even in width; from similar passages in other leaves, and from a few horizontal strokes of ink quickly brushed across it, we know that it is intended as a path, or as steps cut into the rock. (Anyone who has ascended the Tiandu Feng天都峰 “Heavenly Citadel Peak” at Huang shan (Yellow Mountain) is familiar with such a long ascent by rock-cut steps.) Moreover, at the far end of the flat-topped ledge to the right, over a ravine, is a form one might at first read as a stone mass, but which proves on close examination to be a house: the red roof with triangular end, the fence around it, the paving stones leading to it from the left, leave no doubt of the artist’s intent. Are we then to imagine ourselves descending the stone stairway, somehow crossing the ravine, and visiting the house? That is a difficult reading of the painting, but one that seems in the end inescapable.

The Second Leaf, as noted earlier, harks back to a subject and compositional type well-known in the paintings of Wen Zhengming—Wen’s Zhiping Temple painting of 1516 is one of many examplesSee my Parting At the Shore, fig. 113.—even the row of tall pines in the foreground corresponds. But Shao Mi disrupts this familiar pattern by tilting the scene, the right side upward, left downward. The zigzag course of the foreground dike with pines is echoed by the retaining wall across the pond, with the architectural elements of the picture zigzagging more strongly to connect them. Even this leaf, the most conventional of the album in its subject, ends as unsettling.

Leaf Three is another dominated by a sideward-lunging rocky mass. Across from it, to the left, a torii-like gateway marks the starting-point of our imagined passage through the picture, eventually to arrive at the prominent buildings in upper right. A descending path, a plateau with evenly-spread marks—stepping stones?—leading to a stone bridge over a waterfall, more marks, and a steep descent; but there the clear indications of passage end, leaving us to make our difficult way across a deep valley and somehow up to where the stone steps re-emerge, just below the plateau with buildings. What we see is presumably a residential compound where we can rest and commune with the occupant, one of the “immortals” of Shao Mi’s inscriptions.

In Leaf Four both the impressive residential compound and the approach to it are clearly displayed; the structure is surrounded by knobby-topped ridges, open only in lower left where we are pulled abruptly into the foreground. Steps lead down from an opening in the ridge in upper right, bringing us close to the outer wall of the compound, where we find an open gate through which the noble scholar who lives there has ventured out. Leaning on his staff; he stands beneath pines on the shore of a lake or stream. Near him is a stone marker or monument that must have carried some significance for the artist but it remains mysterious to us.

Leaf Five appears to depict, relatively openly, the approach to a residence. Most of the lower right part is occupied by water; two areas of flat shoals suggest places where someone arriving by boat might come ashore. At the lower one, access to human habitation is suggested by a bridge, a fence, and two entrance gates; a path appears above, but with no clear indication of where it leads—a gap between boulders further up is filled with unbroken wall. The same wall extends across the opening between land masses at left top, but here with a gate, through which one would pass to proceed through a grove of tall pines and arrive, presumably, at the dwelling of the “immortal” of this leaf.

The Sixth Leaf is reminiscent of the first, but here the dynamism is played down as the leaf is dominated by a symmetrically disposed, frontally viewed, flat-topped monolith. A path leads in from lower right to ascend the cliff to a place that is reachable also by a long flight of stone steps coming down from a cleft above. From here, a broader path or road, with a protective railing, carries the eye laterally across the main cliff face. It passes behind another square-topped form to arrive at a plateau on which two buildings represent our destination—a shrine? A residence? But how could anyone live in such a place? We can only read the whole “crypto-narrative” structure as evoking once more a difficult passage through the “divine realms” of the artist’s imagination. And even these are ambiguous: is the cleft leading upward from near the buildings to another gap above meant as stone steps? Shao Mi wants these passages to be as unclear in the painting as they must have been in his mind; his hand and brush stop short of clarifying them. Behind both the upper clefts are the pale blue silhouettes of more distant peaks.

Leaf Seven offers less grandeur and less insistent transversals of the scene. Near the lower right corner, above a clearing and leafy trees, a man is seen in a house; another path close to the right margin leads upward to a few houses. No clearly-marked road carries the eye across the center of the composition, but a road emerges left of a vertical mass to lead around the cliff to where a solitary figure, seen below tall pine trees, walks down the road, away from a gate seen high above. He may be coming to visit his friend, the man in the house. Beyond is one of the few distant views these leaves provide.

In the scene presented by Leaf Eight we are again outside a residence, close to a wall made of flat stones of irregular shape; the roofed gate at left seems to invite us in. Red leaves on one of the two large leafy trees outside the gate set the season at autumn. But our attention is drawn instead to a striking form in lower right, a flat-topped rectangular mass of stone set on a slightly larger base. Is it the marker of a tomb, a burial? Again, a prominent form that is ambiguous and evocative confounds any conventional, mundane reading of the picture.

Leaf Nine is another of the striking, grand-scale scenes that most impress, and one that has been reproduced and described. What is immediately disquieting about the composition is the way it all seems to funnel downward, like some unstable, semi-liquid mass, into the lower left corner. Much of the lower right is hidden by fog, which drifts also across the ridge of hills at top. The main residence here, an impressive multi-storey complex of buildings, is located on a flat area just below this; lesser dwellings are glimpsed through breaks in the fog at right. (Depictions of large retirement residences in Chinese painting, of the kind seen here, are often accompanied by clusters of smaller houses outside—living in proximity to simpler folk is part of the reclusive ideal.) How one reaches this “immortal’s dwelling” is relatively clear: a broad road leads in from upper left, skirting the hills to arrive at a prominent structure located near the exact center of the picture, a gateway—or is it a covered bridge?—beneath tall pine trees. There one can pause to gaze at the waterfall or make one’s ascent, by some path not marked but imagined, up to the residence. Always, however, the bottomless gorge into which the waterfall drops seems to pull one’s attention and one’s unsettled imagination.

On the Tenth and last leaf, the inscribed couplet draws attention away from the mountaintop scene, which is accordingly simpler, with only the barest indications of passage and no marker of destination: it is as if we are now departing, not arriving. A railing at the center bottom, marking the presence of a road, continues briefly across a gap in the overhanging mountaintop mass, leading—where? Upward to some unseen higher destination, or leftward around the rocky mass? The pale ink-wash silhouettes of distant peaks draw our eyes, but offer no firm purchase. We are left visually uninformed, deprived of a resolution to this final dream-journey into a divine realm.

Seen this way, studied at length and in detail, the ten leaves of Shao Mi’s album offer visual experiences that must, I believe, have been quite new to viewers of the late Ming. How their strange programs fit with Shao Mi’s temperament as we know of it from written records, whether any of his other extant works offer similarly visionary and unsettling programs, I leave for future researchers to investigate. My own years-long engagement with this remarkable album comes to a close here.

© 2013 by the Seattle Art Museum

Questions for thought

Answers

| Add an answerAdd Answer:

overview

Shao Mi邵彌

Quick Facts about the Artist

Native of Wuxing (Suzhou), painter, poet and calligrapher, collector of curios and antiquities.

A sickly child, who did not undergo the strenuous preparations for civil service examinations and had easy going disposition, possessed an obsession for cleanliness and order.

Talented and appreciated individual who never achieved true prominence, but remained in the shadow of the illustrious and the wealthy.

Member of the “Nine Friends of Painting,” who specialized in painting landscapes and plum blossoms.

inscriptions and seals

essay

Being at that stage in my life when nearly any name, any familiar work of art, calls up a cluster of distant memories, I begin this essay with those attached to Shao Mi’s邵彌 (ca. 1594–1642) Landscape of Dreams album of 1638. It was owned in the 1960s by the French scholar-dealer Jean-Pierre Dubosc, and I may have seen it already when I spent time with him while traveling in Europe in early 1956.